Will Pakistan fall?

Is the wolf really at the door this time?

Washington DC 16 March 2023

This article is cross-posted in Unconventional Nuclear Warfare because the content applies to both newsletters.

Serious rioting has broken out between supporters of Imran Khan and the authorities over allegations of corruption and failures to report to Court. While serious, this is not the greatest problem Pakistan has to address. For the first time, Pakistan may default on its debt, an event that may act as an accelerant to the political crisis, resulting in dangerous outcomes for the region and beyond.

Decades-old political economic problems in Pakistan are coming to a head. The South Asian nation needs billions of dollars in financial assistance to avoid a default at a time when its usual patrons are disinclined to bail it out. The International Monetary Fund is insisting on tough reforms that the fragile coalition government cannot institute without taking a major political hit in an election year. Even if Islamabad dodges this particular bullet, it will have to massively overhaul the way it has managed the world’s fifth-most populous country. If it cannot, then it will further push Pakistan toward a systemic breakdown, which has major consequences for security in the world’s most densely populated region.

So writes Kamran Bokhari of Geopolitical Futures.

Bokhari’s analysis is a very well articulated snap shot of Pakistan today. And Pakistan in 2012, & 2008, & 2003, & 2001, & 1998, & 1977. The reports of Pakistan’s demise have been greatly anticipated, to paraphrase Mark Twain. It has been teetering on the brink for a long time. That does not mean things will remain linear and they will simply continue to stumble along. As America has recently discovered, when instability becomes the national operating system, the chance something radical happens grows. Having said that, instability is not new to Pakistan as it has been for the US. It’s been a feature, not a bug, since day 1. In a perverted way, that brings its own linearity. However there are reasons to believe that taking comfort in the regularity of instability is more hope than judgement. It does not help that Pakistan is already a failed state and a complete meltdown represents a challenge no one can correct. If you thought Afghanistan was complex, tricky, and thankless, Pakistan is orders of magnitude more consequential.

This strategic assessment brief seeks to outline elements of these questions so readers can get a sense of why Pakistan matters, what is at stake, what Thirdoffset assesses might happen, and indirectly, how anticipatory intelligence works.1

The key indicator in Bokhari’s quote above is Pakistan’s “usual patrons [Saudi Arabia, China and the US] are disinclined to bail it out” of a rapidly approaching default. That raises some important questions.

First, the drivers of destabilization have been present for a long time but have failed to trigger a collapse. What needs to be different to pass the tipping point?

Speed matters. Long slowly gestating threats are more readily accommodated than sudden shocks. Pakistan has come close to defaulting in the past but has always been saved at the last minute. To an extent, it has traded on being too consequential to fail. Entering full default would be a new experience. It is unknown if it would be the tipping point, but it seems sensible to treat an event of that magnitude with special caution and concern especially given all the related factors in this case - weak economy, polity, society, stability, a large and significant internal threat from radical extremists, and declining support from abroad.

Pakistan has weathered political shocks in the past - particularly of assassination of political leaders. A widespread economic shock, like a drastic devaluation of the currency, and/or overnight spike in prices of basic daily needs, is more likely to be felt by a wider population base and feed into narratives about the superiority of radical solutions.

Second, would a default trigger a major breakdown in law and order?

As noted above, it depends if the consequences of default are immediately felt by the population. The collapse of the Suharto regime in Indonesia in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis might be instructive here. In the Indonesian case, the devaluation and price of cooking oil turned out to be the final straw for the regime. To the surprise of many, after a period of instability and the loss of territory2, the country righted itself and has since become a successful democratic leaning state. Its economy enjoyed a major turn around and is on track to join the G8 in the not too distant future. This was not a projected outcome for Indonesia in 1998. There are many differences between Indonesia and Pakistan that regrettably augur for a much more violent outcome in the latter case.

Third, is it inevitable that an event of that kind will pave the way for a successful radical uprising?

Pakistan has veteran extremists groups that have been fighting the US, non-Taliban Afghanistan and Pakistan for decades - often with the support of Pakistan. The assumption was with the return of the Taliban to control in Kabul, things would improve for their sponsors in Islamabad. Imran Khan, then-prime minister of Pakistan, described the expulsion of the US from Afghanistan as "breaking the chains of slavery."

Instead of thanks from the Taliban for support against America, terrorist attacks in Pakistan have escalated, reportedly surprising some elites. Having beat America, groups like the TTP appear to feel emboldened to seek the far greater prize - Pakistan itself. Unfolding political and economic circumstances may facilitate an opening.

However, caution is needed in assessing the extremist threat. First, the radicals are not monolithic. A high degree of coordination and cooperation among them may not be assumed. Second, the degree of their preparation to seize the opportunity afforded by a crisis will not be really known until the day arrives.3 Third, it can be reasonably expected that the Army will have contingencies to respond to an economic collapse. Certainly more so than radical groups who may end up competing with one another and undermining the overall radical project. At least in the short term, intra-radical fights might give the Army sufficient time and space to consolidate its power.

The Army

Pakistan was partitioned from India in 1947 to provide a sanctuary for Muslims. The implementation of the split was a disaster and resulted in a religious war with over a million dead. Ever since, Pakistan has been subject to religionist radicalization by well funded and highly motivated foreign and domestic interests. Indirectly, even the US has contributed to this process, wittingly in the 1980s and unwittingly in the 2000s.

Pakistan has been engaged in nearly constant religious wars ever since partition, to include Afghanistan I and II. Neither the Soviets nor the Americans saw their wars in religious terms. Rather they were viewed in statist and geopolitical ideological/proxy terms. That was a major contributing factor to both advanced powers losing expeditionary wars to local tribesmen whose lives were largely unchanged since Biblical times. Just as the British had lost its Afghan wars in the 19th C, as documented by pugnacious war correspondent Winston Churchill in 1899.

The only state institution that can be characterized as ‘functional’ (in Pakistani terms), is the Army and its famous intelligence agency the ISI (Inter-Service Intelligence directorate). Previously a stalwart of British institutionalism, the military became subject to radicalization under Zia-ul-Haq starting in 1977. He is responsible for the still evolving, long, slow, transformation of a culturally traditional quasi-British state institution (the army) into a radical religious Islamist movement, complete with civilian militias and foreign proxies. Our dear friends the Russians helped this trend along by proving an external threat against which zealots could rally - accelerating the slide to a failed state beset by islamists threats. Then we stepped in and did what the Russians did, but better and with more! [It’s now our duty to pass this on to our dear friends the Chinese and let them learn a few lessons.]

What is not well known is the current degree of support within the military for Islamism. If a default on the debt makes the military unable to pay wages (for example) - the possibility of a break in the ranks as the last bulwark of stability in Pakistan might come into play.

Public Opinion

Public opinion remains against the radicals. As Pakistan itself has become more of a target, attitudes have shifted markedly. According to a Brookings study

Pakistanis’ views of terrorist groups are not as extreme as you may expect, but while Pakistanis are negative on militant groups and their violence writ large, their wider narratives surrounding these groups are far from simple. They clearly recognize extremism is a problem—82 percent of respondents in 2015 said they were concerned about “Islamic extremism” in Pakistan—yet their narratives on extremism are muddied by a sense of national victimhood, by a blindness toward Pakistan’s own faults, by anti-American and anti-Indian sentiment and a deep-rooted sense of a struggle between Islam and the West. Adding to the confusion are strong ideological and religious convictions and positive views of Islamic law, which lead to sympathy for militants who claim their goal is to impose Sharia in Pakistan.

Prime Ministers and Presidents regularly fall afoul of succeeding political regimes. Former President Musharraf recently died in exile. Former PMs have retuned from exile to varying degrees of welcome. Some have been shot.

Imran Khan is perhaps a different case - having been a cricketing legend he has become a populist leader engendering an uncommon passion among his supporters. His movement’s response to actions taken again their leader has a January 6 feel to it. Combine Khanism with a default that hits the man on the street hard and creates turmoil in the army, and the threshold of stability might finally give way.

What does a successful radical uprising look like?

It can take a number of forms. The key objective is to seize control. Are all the disparate groups that make up what we might call the Pakistan Taliban (hereafter PT) able to coordinate?4 Will they be able to quickly and comprehensively overcome the Army at key strategic points - military bases, weapons depots, intelligence HQs, police infrastructure, major media outlets, transport hubs, and so on. Does the PT enjoy sizable insider support in the security apparatus? Next, could elites prevent or reverse a PT coup? How would Pakistans foreign sponsors react? Would they send troops? How would India react? Would it initiate a preemptive war?5 Have the PT factored in all of these considerations and have plans to address contingencies? Pakistan could become a heavily armed terror state.

It is doubly ironic that one of the reasons the continuation of US patronage of Pakistan is in question is because the US itself will almost certainly be forced to default by its own radical extremists in Congress, many of whom are religionists whose thoughts, words and deeds are essentially the same as the Taliban just with different branding.6

Why Pakistan Matters

According to analysis presented in the Pakistani Armed Forces magazine

Pakistani economy is currently trapped in low growth, high inflation and unemployment, falling investment, excessive fiscal deficits, and a deteriorating external balance position.

Pakistan matters because it has a huge population dominated by a youth bulge, difficult to control mega-cities (10m+), ungoverned tribal areas, a democracy in name only, weak state institutions, a poor resource base, a broken economy, massive financial and political corruption, food-water-energy nexus stressors, low literacy, and abysmal levels of opportunity.

Why Pakistan Really Matters

If all of these reasons were not enough to make Pakistan matter, there is one factor that overrides all others. Pakistan possesses nuclear weapons held under questionable security and safety conditions. The physical security of its nuclear weapons is low and warhead safeguards are suspected to be minimal or non-existent.

‘Physical security’ refers to where and how the warheads and delivery systems are made, moved, stored and deployed. That is the tip of the iceberg that includes doctrine (training, techniques and procedures) for each stage of the weapon cycle, and so on.

‘Warhead safeguards’ refers to ease of access to, and complexity of, the triggering mechanism. US systems have extensive “permissive action links” or PALs, that are defined as

A device included in or attached to a nuclear weapon system to preclude arming and/or launching until the insertion of a prescribed discrete code or combination. It may include equipment and cabling external to the weapon or weapon system to activate components within the weapon or weapon system.

The concern with Pakistan's weapons is we are not certain they have any PAL protections and we know that many other elements of their protection programs are minimal or non-existent.

Even in America’s case, none of these systems or protocols are perfect. We have just been lucky. One of the best known physical security failures happened in 2007. B-52s departed Minot AFB and flew across the United States with armed nuclear weapons. No one in the chain of custody realized this had happened until the ground crew servicing the aircraft after they landed in Barksdale AFB looked into the little window on the side of the air launched cruise missiles and got the shock of their lives. The window was ‘red’ not ‘green’ for an inert training weapon. Somehow, the real thing was taken out of storage, loaded, and flown across the US and no one was the wiser. The warheads were not reported missing nor were they protected by the various mandatory security precautions as they sat on the tarmac unguarded at the sending and receiving bases - until discovered.

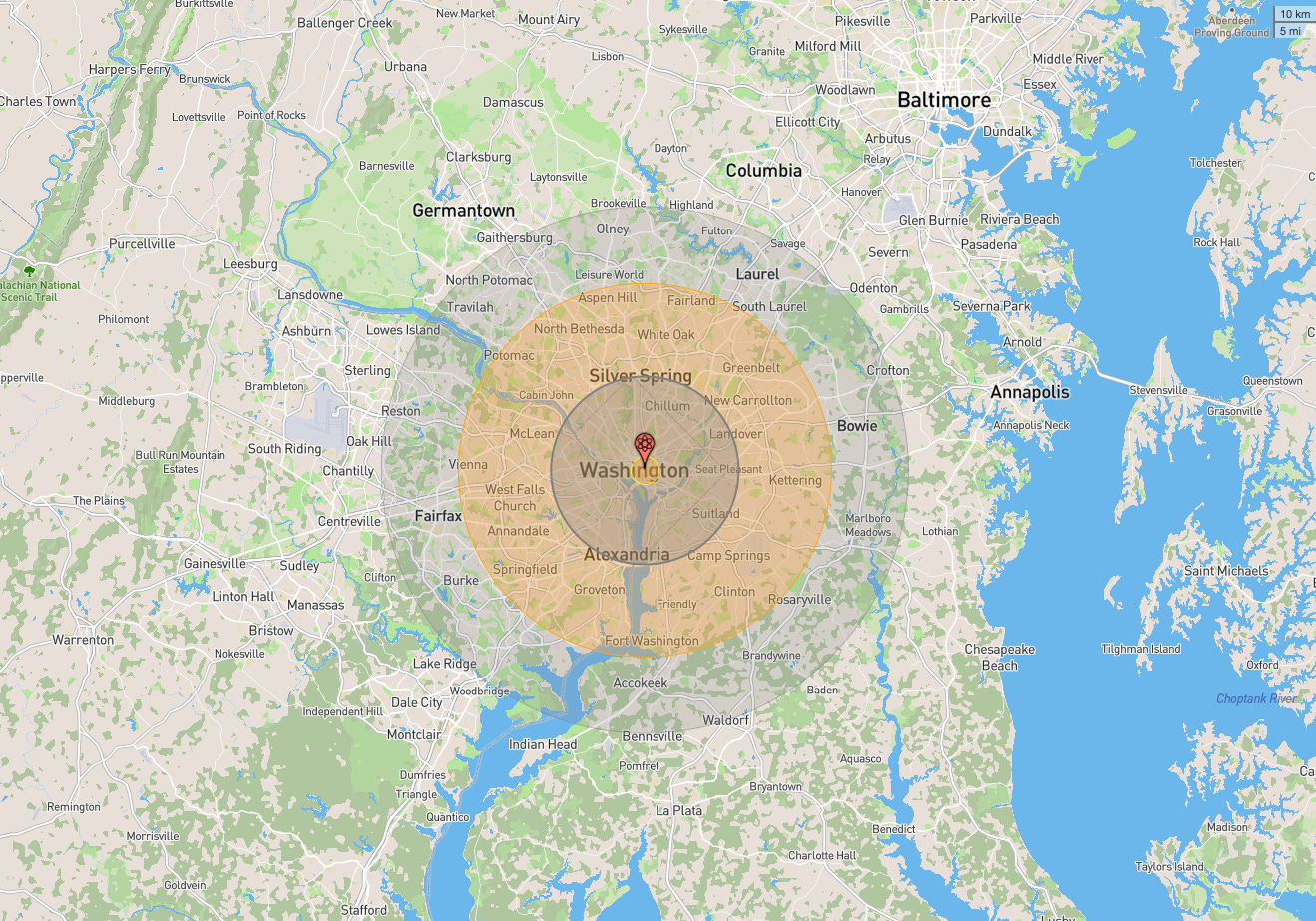

We have had even worse luck with warhead safeguards. The Goldsboro incident is a useful illustration. A 4 megaton thermonuclear W39 warhead was accidentally dropped on Goldsboro North Carolina in 1961 when a B-52 broke up in flight.7 Four of the five PALs failed. A detonation was prevented by the last safeguard. Had it failed like the others, a good portion of the eastern part of NC (and those parts of Virginia downwind) would have simply disappeared and/or been rendered uninhabitable for 24,110 years - the half life of Plutonium 239. For comparison, below a Hiroshima bomb is compared to the Goldsboro bomb using Washington DC as the Index city - the inner 2 rings are bad.

Over-engineering prevented an unimaginable catastrophe. This was not the only such accident. In fact, the US has a pretty startling record of near-misses of this kind. It is truly a wonder we have avoided a detonation thus far. Nor does this account for accidental-war 'close-calls', which has its own shocking record.8

Lose Nukes

Any crisis in Pakistan that exposes its nuclear warheads to an elevated risk could not be tolerated by external powers. India, Iran, China, and the United States all have immediate but very different interests at stake in such a scenario. All would perceive a direct threat from nuclear armed Islamists. India, with bitter memories of partition onward, would fear an immediate nuclear Mumbai without provocation or warning. China, already deeply concerned about radical islamism on its western borders, would not risk its agitated minorities aligning with Pakistani terrorists and threatening Beijing. Iran, a shiite state that shares Baluch separatists on both sides of its border with Sunni Pakistan, would sense a threat but it might also seek an opportunity in the chaos to attempt to steal a warhead or two. That is highly unlikely but past a certain level of collapse, an audacious raid might have some chance of success. It’s hard to imagine the IRGC have not considered such a scenario. Unlike the other countries, the US is out of range of a missile attack. But that does not diminish the interest the US would have in restoring order to the international system by securing the threat.

It is conceivable that China, India and the US all have contingencies plans to mitigate the threat of Pakistans warheads falling into the wrong hands. It is unlikely that they have coordinated these plans or would do so on the day. How any of them could make it onto the ground and conduct a successful render safe or removal operation in the middle of nation-wide turmoil is hard to imagine. This is compounded if the weapons have already been seized by extremists and dispersed - likely into major cities to become needles in the haystack of multitudes.

Past render safe or extraction, is compellence. Coercing extremists holding nuclear weapons to give them up is not in the traditional deterrence playbook. A coercive approach in that context, say by India, might take the form of a preemptive strike, given they have no defense against a nuclear armed dhow sailing into Mumbai harbor.

We never really understood Identity

The Pakistani military is both the bulwark against the Taliban and their creator, sponsor, financier, armorer, and cheer squad. It is a duality that Americans simply cannot grasp because it is outside of our cultural understanding and experience. Post Zia, the military has been on one slow long slide from a normal developing world institution of state, through a sponsor of terrorism against Pakistan's allies (US and in the future, China) as well as enemies (India - where Afg was a proxy battleground between the two and anyone else who got caught up in it), to possibly being on the precipice of falling to, divided by, or cooperating with, a radical islamic terror group in charge of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons.

At its core, the US made a categorical mistake. We were statists seeing the world through a statist lens which encouraged us to mischaracterize religionist enemies as discreet terror cells in various states that were the responsibility of local authorities to suborn. A statist is defined as "an advocate of a political system in which the state has substantial centralized control over social and economic affairs". Whereas religionist is defined as "excessive religious ardour or zeal, extreme piety, discrimination or prejudice on the basis of religion or religious beliefs" where religion supplants a constitution and laws as the basis for governance. In essence, we forgot that the Treaty of Westphalia created states to reign in religious wars. The state + capitalism had worked so well for us, that we failed to understand how, where, when and why it failed others. Therein lies long term strategic surprise.

In the Cold War the Soviets had to be stopped at all costs because they represented hair-trigger global nuclear annihilation and, short of that, they had something we could understand - a huge conventional military. By comparison, the Muj were perceived as just a bunch of angry backwood hicks who could be used to erode that huge military for our own benefit (esp in Europe) for penny’s on the dollar while not risking American lives and global thermonuclear war.

The pitfalls of being the enemy of the Muj's enemy were concealed by ahistorical, areligious, apolitical and fundamentally statist thinking in DC. We took the wrong lesson from the failure of Arab nationalism to unite the Arab world.9 We assumed that Islamists would likewise fail to get their act together. Additionally, the Muj fighting the Soviets were OUR JIHADIs and could NEVER be a global threat like the mighty Soviet empire. So we aligned with the lesser of the two evils. It also fit various domestic American narratives, including Christian religious fundamentalists who identified with the Muj because they had a common enemy in the Godless communists.10

It's not like we didn't have experience dealing with islamic terrorists in the 70s. Perhaps because of that experience we underestimated them. Beirut should have taught us something more significant was afoot. We saw Afghanistan through our own statist lens. We assumed it was a re-run of Vietnam, but this time the good guys were on our side.

The problem with this pattern of thought is it conceals an important difference - Vietnam was a political war driven by nationalism, while Afghanistan (both times) was a religious war driven by biblical enmity against an unwanted foreign occupier. DC did not imagine that moving from one large predictable traditional enemy state with nukes - to a hydra headed multitude of unpredictable radicalized non state enemies with potential access to nukes - was even remotely possible. Yet here we are.

Godlessness is Good

Islamists and Christianists believe jihad, or the rapture (mass death), will take all believers to a much better place (with or without virgins according to interpreters of scripture here on earth). Hinduists believe in reincarnation. When everyone has adamant faith death will bring on better times, that is not a basis for stability when nukes are involved.

Guess who does not share this faith-based enthusiasm for mass death as a pathway to a better world? In the past, it was the Godless Soviets. Today it is the Godless Chicoms and the remaining minority of Godless secularists in all branches of the USG and civil service. As a consequence, ironically enough, whether they know it or not, US secularists in government have a closer shared intellectual affinity for the Chicoms than our "traditional" ally Pakistan.

Being in a region does not equate to alignment with prevailing identities. It can be a powerful source of difference and thus enmity. China and Pakistan have long been allies because of their mutual antagonism towards India. Importantly, the nature of the antagonism has been fundamentally different. For China, territorial and geostrategic. For Pakistan, religious.

China has a deep-seated fear of religious fundamentalists, particularly islamists. Xis crackdown on the Uighur’s belies his #1 strategic threat - internal security. That is far ahead of border skirmishes with India in the Chinese calculous of threats. To the Chinese mind, the Uighur's are a consequence of zealous religious ferment in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Any threat, real or perceived by China over fast moving events in Pakistan may sharply change the character of Sino-Pakistani relations, from one of cooperation to antagonism. There are extreme scenarios in which China might engage in robust containment of, or even intervention in, Pakistan.

Thus the choice in the US and abroad is between religious fundamentalists v state-power secularists. This will make for new informal alliances and relationships. Herein lies opportunity for America if we can get out of our own way.

Update 26 June 2023

Pakistan’s Military Fires 3 Commanders, Cracking Down After Khan Protests

They were among 18 officers disciplined for their handling of protests by supporters of Imran Khan, a former prime minister, sending a message that support for him would not be tolerated in the ranks.

Update 13 July 2023

Pakistan army says it lost 12 soldiers in militant attacks

Update 9 Aug 2023

Most states have armies. In Pakistan, the army has a state.

A decade ago, Pakistan observed its first peaceful transfer of democratic governments, and there was a degree of hope among some analysts that the military was slowly receding into the background of the country’s political landscape. But that proved short-lived.

Khan, a national cricket hero turned populist rabble-rouser, operated in the fringes of the country’s political scene until he and his Movement for Justice, known by its Urdu acronym PTI, managed to break into the mainstream in the first half of the decade.

It’s widely believed that his rise was enabled by elements of the military, which Khan lionized while denouncing the venality and decadence of the country’s entrenched civilian political elites.

Though a cult figure for his supporters, Khan was seen by critics as a demagogue and would-be authoritarian, who demonized political opponents and mismanaged the country’s affairs.

In April 2022, he was forced out of power by a no-confidence vote in Parliament that likely had the tacit backing of the military, which had lost faith in Khan’s governance.

“Khan and the military also appeared increasingly divided on foreign policy. In March last year, Khan accused the U.S. government and Pakistani opposition of conspiring against him, prompting U.S. denials and dismaying the military leadership that was seeking to maintain a working relationship with the United States.”

Thereafter, Khan was beset by an avalanche of dozens of legal cases against him.

The military’s backlash has been merciless. Thousands of PTI supporters have been arrested, with some facing prosecution in military courts. Dozens of PTI politicians, fearing arrest, have quit the party, while others have defected to different factions and condemned Khan’s behavior. Sympathetic voices in the media have gone silent or been silenced.

“The Pakistani Army is yet again engaged in political engineering by forcing resignations from Khan’s party and steering together new political forces,” political analyst Arif Rafiq told the New York Times in June. “The primary aim here is to remove Khan from the political process, as he’s no longer reliably obedient and has amassed popular support that gives him political capital independent of the military.”

Khan’s distinct brand of politics — and popularity — may make him a unique threat to the top brass. “Once the army’s proxy, he has now gone rogue with a vengeance and is trying to tear apart the military’s institutional integrity by sowing dissension in its ranks against the army chief,” wrote Aqil Shah in Foreign Affairs. “The army is also probably concerned that Khan finds his main support base among the traditionally pro-military urban middle classes in Punjab, Pakistan’s largest province and the heartland of army recruitment.”

This is not a comprehensive assessment. Thirdoffset has followed Pakistan for over a decade. It is a wicked problem.

East Timor was illegally annexed in 1975 but was nevertheless perceived domestically as sovereign Indonesian territory.

They have experienced significant successes in the past, attacking military and intelligence bases. The attack on PNS Mehran and military HQ in Rawalpindi are two of the most notable due to their scale, duration and casualties. It is not known if similar operations have been mounted at nuclear weapons facilities.

There are many groups - this is just a generalized shorthand. It would be a mistake to assume unity across groupings which is a factor mitigating against organization of a successful uprising. Currently the TTP appears to be the dominant group.

Bearing in mind PT forces (and the ISI) were behind many terror attacks in India including Mumbai. The Indians could rightly expect a major uptick in attacks if the PT take control of the Army.

The Hiroshima bomb had a 15 kiloton warhead. Mega>kilo x 1000. Put another way, their blast energy in equivalent weights of the conventional chemical explosive TNT, is as follows: a kilo ton is 1000 tons of TNT. A megaton is 1,000,000 tons of TNT.

By far the best book on this issue and an excellent and highly readable history of America’s nuclear weapons and doctrine is Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control.

Arab nationalism failed to unite the Arab world which was something we could see but did not understand (outside of a few specialists at CIA and the universities). Remember when Gamal Abdel Nasser was going to be the Hitler of Nth Africa? We did not understand the failure of Arab nationalism because it was a statist overlay on a non-confirming cauldron of identities.

It turns out that Arabs are not all the same! Imagine that! In fact, most people in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are not Arabs! Many Egyptians do not identify as Arabs. The people of MENA may speak derivations of Arabic and support one of the many derivations of Sunni Islam, but they are not all descendants of the tribes of the Arabian Peninsular. Far from it.

On top of all that, the "other half" of the Islamic world, the Shiites, identify in opposition to Sunni Arabs both in religious, cultural, and nationalist terms. Beyond that, the majority of the worlds adherents of Islam live in Indonesia and neighboring SE Asian states - far from MENA - and their form of Islam is different again. To all of this vibrant difference, South Asian forms of Islam must be added.

Amid all this non-conforming identity 'chaos' it was easier for statists in the west (and many running states in the Islamic world) to simplify everything into states. It was not a good fit. But it was the only game in town until bin Laden and the boys forced us to think about Islamism in different ways.

States are not the same as nations. There are very few actual nation-states. (Today, maybe only Japan truly conforms to the classical definition. France and Britain no long fit the definition, if they ever did, as the masses of their former colonies sought a better life in the mother country - including over 1.5 million people of Pakistani descent in the UK). The fake concept of 'nation-state' confuses understanding of the complexity of the above permutations of identity.

Pakistan is a classic example of a state struggling to have authority over empowered aggressive competing nations and religious sects within their borders. The identity of being Pakistani or an adherent of Islam is further complicated by regional identities - the Baloch or Pashtun and so on. However, it is also true that the vast majority of Islamist extremists in Pakistan are Sunni Pashtuns. As was the case in Afghanistan. Lines drawn on a map in London in the 19th C, mean little to them. Imagine! It took us a long time, blood and treasure, to relearn this.

Pakistan of course had a role in all of this. It sought to play both sides, in order to gain an advantage against its “true” enemy - India.

Well I guess that answers my question, which you can disregard. It genuinely appears the human race may be on its way out. Hey, when we're all gone, maybe in a few hundred thousand years after it's finally healed, the earth can do dinosaurs again, dinosaurs were cool, right?

Oddly, when I was a kid, reading all kinds of science fiction, I'd kind of romanticized living in the "end times", or some post apocalyptic world, I never really expected to be living in it, but it seems every day we get a little closer.

I was raised Catholic, though due largely to reading all that SF from the age of about eight, I never really believed any of it. Given my father was feeding me those books, I think he only ever went along with it for my mom's sake.

You'd think three thousand years of human progress would be enough to shake people out of the religious insanity, but I guess not. To me it was always just history, the thousands of gods that came before the current crop,. The only reason this one's hung around so long is that we no longer need to invent new ones to explain shit, this should be obvious.

All of this only serves to prove that religion has always been more or less political systems of control. I kind of always figured nuclear annihilation would come out of religious extremism. Blanding bronze age moral philosophy with 21st century destructive technology, what could go wrong?

What a world....